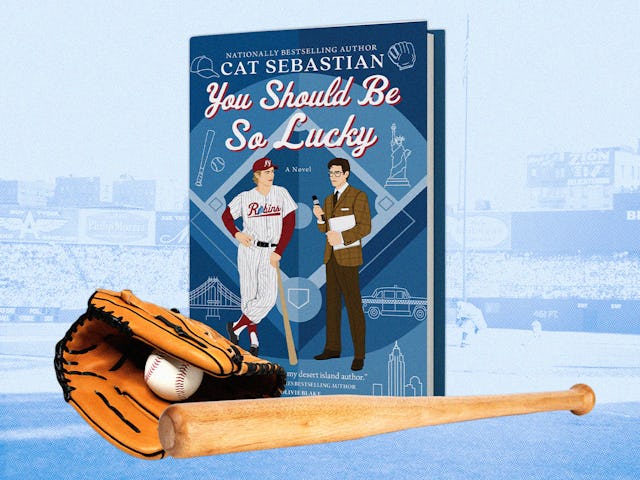

Your Queer Historical Romance Of The Summer Is You Should Be So Lucky

“I think romance is often the fantasy of being seen for exactly who you are and being loved for it, right?” says author Cat Sebastian.

Author Cat Sebastian got her start writing queer Regency romances that played with one of the oldest and most storied subgenres in romance. And then, around the time of the pandemic, she tried a little something different — a series of novels and novellas set in midcentury America. And folks, I simply cannot get enough of them.

Maybe it’s because she often characterizes them according to the amount of “crying on the floor in sweaters” each one contains. (Who among us hasn’t spent some time in the last four years crying horizontally? Though let’s get real, it was ratty sweatshirts.) Maybe I just watched too many Turner Classic Movies at a formative age. Whatever the reason, they are delightful, and her latest — You Should Be So Lucky — is no exception. A loose sequel to We Could Be So Good (which followed a pair of reporters slowly falling in love), it features the budding relationship between a grieving reporter named Mark, who’s been maneuvered into covering a floundering new baseball team, and Eddie, who should be their star hitter, but he’s in a terrible slump.

I wanted to ask Sebastian about what makes a scene romantic, her decision to write queer romances in the era leading up to Stonewall, and also about her recently announced upcoming contemporary novel, which she describes as a love letter to shows like Star Trek and Stargate: Atlantis. So we scheduled a chat.

Scary Mommy: Give me the elevator pitch for your latest.

Cat Sebastian: So it's about a grieving reporter who is assigned to cover a slumping player on an expansion baseball team in New York in 1960.

SM: I have to tell you, I thought I was going to cry a lot more than I did while reading this book.

CS: I think it depends on what makes you cry in a book, right? I think that some people find being seen and being comforted to be the stuff that they get emotional about and they cry over it, but not from sadness necessarily. But I'm a person who just cries. I cry really indiscriminately, so I don't even need a reason. By the third act, if I get to the last 10% of a book, I'm probably crying.

SM: I think I was expecting to be more sad, and then it ended up I was just so happy for the characters that they got to know each other.

CS: I mean, it is a book that's about finding comfort in someone else and finding comfort in the experience of someone caring for you, and that's a theme I like a lot. I keep going back to that theme. One day I'm going to have to find another theme. But right now I like looking at that from different angles. It's really very soothing, and I think that's one of the reasons why romance novels can be really appealing.

I've been thinking a lot about how there's always a reason why we read whatever subgenre we're reading, right? Maybe it's for an adrenaline hit — if I'm reading a thriller, there better be some real messed up stuff, and I want the rush of figuring out what it is. If I'm reading a mystery I want, it's not solving it. The fantasy being delivered with mystery is often the fantasy of justice, the fantasy that we can live in a world where justice exists. And I think romance is often the fantasy of being seen for exactly who you are and being loved for it, right?

SM: How did you end up moving to writing mid-century historical romance?

CS: I like the time period, is really where it started. Visually I love it, and I knew that I wanted to write something in it. So my friend Olivia Dade was putting together an anthology and she asked if I wanted to contribute a novella, and I was like, ‘What if I wrote a 1959 set second chance romance?’ And she was like, ‘Sure, do literally whatever you want.’ And so I did. It was so fun to write. People liked it. And that sort of stuck with me. And then when the pandemic happened, it was March or April 2020. I have my kids in the house, their dad in the house. It was terrible. The house was too small and I couldn't write the book I was supposed to write. And so I was like, ‘As a palate cleanser, I'm going to write another novella in the same universe as that previous Cabot novella."‘ And that, again — road trip, minimal plot, high chili pepper/heat level situation — was so fun to write.

People really liked it. That’s when I started thinking, ‘You know what? I think I might have the numbers here to make a case for publishing a book in this era.’ And so instead of assembling the numbers, I just wrote We Could Be So Good.

I had written maybe 12 books set in the 1700s and 1800s, and I was a little tired of it. If I needed to keep writing in that era, I could have, but given a chance to take a break and do something different, that was really, really tempting. And I know that there are a lot of authors who can write dozens of books set in roughly the same setting and time period, and that's a talent that I think I don't have. I need to chase after the new shiny thing. And so it really was very refreshing to write something in a brand new setting.

I feel like there's something going on with the fact that around the time that I started writing, historical romance was really synonymous with Regency. Now it's less so. I feel like we're starting to see a little more variety, and I think that might be because the historical market is pretty soft. I’m looking now and it’s like, "‘Oh, that's a medieval. I haven't seen much. That’s a pirate romance. I haven't seen those in 20 years.’ It's an opportunity for the genre to revisit what it considers to be a normal setting.

SM: You're writing about the pre-Stonewall era. I think that a lot of people would assume that this would be a sort of sad time to write about, but your books are totally life affirming.

CS: One thing I kept thinking about is that in order for Stonewall to happen, you need to already have a community. Stonewall happens because you have a bar that had regulars and they knew one another, and so when some people were being arrested and harmed, other people made it into a protest.

You're coming out of the '50s, which were really, really bad. The '30s had been not too terrible, and the '40s, because of war reasons, you have a little bit more leeway. And the '50s became truly terrible. And emerging from that, you have people who are also looking at the Civil Rights Movement and saying, ‘That could be us.’ And are deliberately organizing, and you also have people who are just forming a community out of necessity. You have sex workers, you have people who are doing drag. So you have this building block of what the queer liberation movement was made from. Writing about the period of time when this was starting to gel, I love that.

Also, when we think of what the '50s are, at least in America, we're thinking of aggressive domesticity — white picket fence, sitcom, stay-at-home mom, kids and a dog, whatever. That's something that was only available to certain people. Obviously straight people, but also white people, rich people, right? So I want to share a book where — for We Could Be So Good — aggressive domesticity is part of that. They want that. They want domesticity. They love the idea of there being somebody to come home to, which is sort of queering the entire experience.

One thing I kept coming back to was the idea of, in all my books to a certain extent, but especially the books that get closer and closer to the present day, the idea that when you insist on doing for yourself, that is an act of protest. When the norms of society are telling you you don't deserve it, or maybe you don't exist, and you insist on having joy, having a full life, that's empowering. And I think that obviously we currently live in a time that's not fantastic for a lot of queer people, and that does not mean that everybody's lives are soaked in tragedy. Counting the wins as wins and carving out joy for yourself as part of what marginalized communities have always done. And that doesn't detract from the oppression they experienced, but writing about that is for me affirming.

SM: I want to hear you talk about what makes something romantic, whether that’s a whole book or just a scene.

CS: Part of it is as I'm writing the book, I know that I'm writing a character study. I know that that's the strength of what I'm bringing to the table, right? And so whatever I do to make it romantic needs to be deeply embedded in what these two characters’ personalities are, or it's not going to work. If you're writing a book that has really, really high tension, what is going to be romantic might be totally different from what it would be in my book.

SM: Did you start out like, ‘I'm going to write a book about putting your life back together?’

CS: I knew I was writing a book about what happens on the other side of rock bottom, whatever that means for you, and also about the existence of second chances. I knew those were going to be two. I knew going in that they were going to be in some way shape or form themes or keys in the book.

I do think it's a really common experience of writers — you look back and you're like, "Oh, I made a pattern." But in this book I knew that loss very broadly speaking and feeling like you’re at your lowest low and not believing there’s something that comes after it, and then sort of accepting that this is actually what life is. Life has its flows — it's not a new concept — but being able to experience it not as something you deserve, maybe not even a tragedy, but that it is something that you can just accept as “this happened,” and then find that there are other good things.

SM: I really enjoyed reading the idea of like, ‘Well, you know what? Sometimes you have a string of misses, and that's just life, but that doesn't mean life is over. That doesn't mean you don't crawl out of rock bottom.’

CS: And it doesn't even mean there's a reason. I think that that's one of the most frustrating things when you have a bad experience, you so badly want there to be an explanation whether it's losing your job or if you get seriously ill. People want there to be a reason and they will say the wildest things in order to make sense of it.

And probably you're doing the same exact thing yourself. You are trying to find meaning in the bad thing, and there's often no meaning at all because there's no narrative at all. It just happened, it's random. The loss of Mark's partner, there's no reason for it. It just is a really bad thing that happened. Eddie's slump, I didn't want to explain why it happened. Various characters have various opinions, but it just happens, slumps actually don't usually have a reason unless there's an injury. It's a statistical thing that happens, and I wanted that idea of meaningless loss to be part of it.

SM: Sometimes you just get hit by an asteroid. What are you going to do?

CS: Exactly. It's just a fact.

SM: Changing gears a little bit, I want to ask about your next book, which I am sure you cannot talk about it too much, but I want to ask you on a scale of one to 10, how much of modern fan culture is literally built on Spock’s facial expression at the end of “Amok Time” when he realizes that Kirk is not dead? I'm giving it 85%.

CS: No, for real. I feel this is one of those butterfly effects. If you don't have that episode with every line reading identical to what it is and Leonard Nimoy's face doing exactly what it was, we live in a different world.

I had watched as a kid all of Star Trek, the original series, because it was one of the shows that was on television when I was home sick from school. And not until watching them in my thirties did I realize exactly what was going on. I knew that the history of romanticizing two characters together as a community probably had its origins with Kirk and Spock. I knew that, but at that point I was so used to the experience of taking two characters and making up an entire love story for them in my little head, that to see that it was on the screen was something I felt I could not get over.

SM: It was not made up. It's there. I don't know if they meant to put it there or not, but I saw what Leonard Nimoy’s face did, and it's text.

CS: I think that he is such a deliberate actor that he knew what he was doing. But yeah, I love that, and I love that people have that and then they see The Wrath of Khan, 15 odd years later, and they correctly perceive that as a love story. And the only thing to do about it is write millions of words of fanfic and do art and make your little fanzines in your basement using your mimeograph machine. A community is born from it, and I love that, where people are seeking one another out saying, ‘Did you see this?’ Loving things in a community with other people who want to do these extremely close gay readings of the text is fun. That's such a common queer experience. I love that, and I love the intersection of queerness and sci-fi. I’ve had a ball with this book.

SM: So do you have any book recommendations? Things you've read recently, things that have come out recently, things that are upcoming?

CS: I strongly recommend T.J. Alexander's Triple Sec. It's a poly romance, it is just so fun. The side characters are exquisitely drawn. I love every single thing T.J. Alexander writes — every time I get to the end of the book, I think to myself, ‘Why aren't there 300 more pages?’

I recently read In Memoriam by Alice Winn. I didn't expect it to be a tearjerker with an optimistic ending. It's a war tragedy book, and I cried my eyes out the way you do when you're watching a sad movie, that type of thing where you can almost hear the music that's going to make you cry. But it's not not a romance novel — it has the same beats that a romance novel would, but it's a love story with an optimistic ending. I loved it, and it's also, I feel like an example of how historical romance can work in a different way. It's an unusual setting, with different beats.

I also really love We Could Be Heroes by Philip Ellis. The premise is that the gay actor needs to stay closeted in order to keep his role in a superhero franchise movie. But it's also about the very queer origins of the superhero. I loved it.

I’m currently reading All the Right Notes by Dominic Lim, which I’ve had on my TBR since it came out. It turns out the book is one of those books where the voice is so strong, it doesn't even matter to me what’s going to happen because the voice is perfect. It's like pulling me through the book and the character's voice is so funny and occasionally so sad that the range is exquisite.

SM: Ok, now give me three fanfics!

CS: I can't only do Captain America fanfics, that's not going to happen. “Graduate Vulcan for Fun and Profit.” It's all about Kirk at the academy. It's a total delight. “Strive Seek Find Yield” by Waldorph, which is another Star Trek, but it's a royal AU, which is not something I usually enjoy at all, which is perfectly executed. And now let's go back up to Captain America. I think “20th Century Limited,” by Speranza.

I want to think of 10 more immediately. Those are good. I feel confident about those three.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and length.