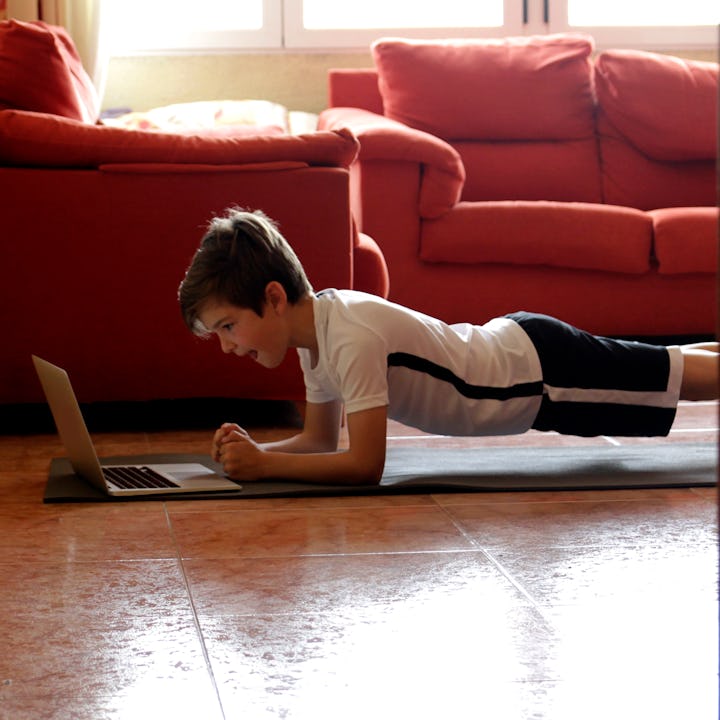

My Tween Wants A Six-Pack. How The Hell Should I Handle This?

Combatting the pressure to be perfect is a battle for so many young people.

I took a picture of my son, age 8, and his three friends on a hot summer day, running through the sprinklers. It was a sweet moment of summertime bliss, the kind of split second in time that captures their mostly carefree childhood. That is until I saw the picture later and noticed my son's stomach was sucked in — like, way in. His ribs were sticking out, and his back was arched. Clearly, he was striking a pose, but not the silly way his friends were. So, I asked him what he was doing. He casually said, "Oh, I'm trying to show I have a six-pack."

Of course, as a mom, it's one of those moments when your heart hits the floor a bit, one of the thousands of heartbreaking instances we experience in which we see society rubbing off on our precious clean slate of children. And he's one of four more kids to follow.

Devastatingly enough, roughly half of kids in the U.S. already report feeling self-conscious about their appearances as early as the 8-12 age group, and other studies sometimes show earlier. It's also a sign of the times in which evidence is pointing to rates of eating disorders increasing much faster for males than females.

My son had never changed his eating habits to "improve" his body, and he'd never mentioned feeling self-conscious, either. But clearly, he was. I asked who has a six-pack that he wants to be like. Then I found the culprit, among others — "Every NFL player on YouTube, mom."

I tried dropping some knowledge that certain positions such as centers, defensive tackles, and nose tackles very rarely have six-packs. But it didn't matter that Joel Bitonio, a Browns guard, has nowhere near a six-pack but is at the top of his career. Same for Creed Humphrey or Quinnen Williams. My son was already convinced, at age 8: A six-pack (or more!) was a must.

Beyond the videos, he'd likely have encountered the same narrative that men should be trim, cut, and powerful. So, what's a parent to do? I asked experts for some insight.

Find your child's "why" before responding.

Eating recovery center clinical psychologist Amy Gooding suggests parents approach this topic cautiously. "There are a number of reasons why a person may desire to change their body. They may be trying to improve athletic performance; feel stronger, leaner; achieve some body ideal; or it could be related to social comparison or acceptance," she says.

As I feared, she points to "lean, chiseled bodies" in the media as the start of idealizing a body type, which can lead to a critical inner dialogue and, ultimately, negative thoughts that make them want to change their bodies. For my son, professional athletes (and his quest to become one) were behind the photo.

Focus on the body's amazing ability to perform, not look good.

We've heard it often in body positivity declarations: It's not how your body looks, but what it can do.

Trevor Thompson, a former U.S. Navy SEAL, is an Alaskan assistant guide, skier, climber, and base jumper. He uses the terms "form" to describe physical appearance, and "function" to describe physical ability.

"Form follows function and is most important. Your physical and athletic body and the way it looks is a result of genetics first, followed by your effort. You should be proud of the effort you put in and how it shows, from airing legs to full lungs," he says. "I am always impressed that the most capable are not always those with showy forms. It can be the case, but don't think that for a moment your six-pack or biceps will impress a hard-working outdoor or fully-rounded athlete or champion if you cannot also compete and perform. Nobody would buy a Ferrari with a crummy, underpowered, slow-geared engine just on looks."

Educate kids about the actual human body.

There's a reason not many of us have a six-pack — not everyone is even physically able to achieve it.

"Similar to achieving a thigh gap in females, body type and genes have a lot to do with it," Gooding says. "Working out and reducing belly fat can only do so much. For some, their abdominal region is structured so that they are unable to achieve visual six abs." She adds that a "misguided person" may go to great lengths to achieve these "body ideals," but their bodies are simply unable to achieve them, leading to dangerous dieting and exercise.

So, I increased the types of NFL players I was showing to my son, along with other successful athletes who don't have six-packs but are elite performers beating records.

Tips, Tricks, and Tools to Encourage Your Kid's Healthy Body Image

This is one of those parenting projects, and an important one, that our experts say is part of the long game. Here's what they recommend.

Winning can be important, but it's not the only acceptable outcome.

If being the best is the most important thing in your household, having the ideal body may be quick to follow (with all the issues it brings). Thompson says of his father: "Being competitive, keeping after a pursuit till the end, and not quitting were paramount. Did he say winning was important? Yes. Was it the only result acceptable or able to be stomached and learned from? No."

Turn the mirror around.

If you are bad-mouthing or trying to perfect your own body, Gooding says your child picks up on it, absorbing those messages themselves.

I had to check whether I'd complained recently about my own postpartum belly, or whether I'd expressed gratitude in front of my sons for what it had done for me and why it was like that (I focus on calling it my baby's old apartment rather than my still-pregnant looking belly these days).

"Parents should not comment on other's bodies or their own," emphasizes Gooding. "They should work to be a positive model of acceptance of all body shapes and sizes."

Get picky about their media consumption.

Gooding says there's monitoring social media, but there's also intentionally unfollowing or limited exposure to influencers, fitness and nutrition sources, and suggested content on their apps. As a mom, it seems intimidating to try to overrule the algorithms choosing profit over my kid's health, but necessary to try.

DMoose founder Mussayab Ehtesham is a business owner who built a fitness brand focused on balance and body image issues.

"This shift in content consumption reminded me that those 'perfect' images in the media are often highly edited and don't reflect reality. I try to follow motivational speakers as well, and rather than having my social media feed full of useless content, I consume content that amplifies my abilities and increases my knowledge," he says.

Make more comments on just about everything else.

If you make a big deal of relational, academic, and performance achievements over how bodies look, kids will take notes. As Gooding puts it, "It should be the least interesting thing about us."

While we can't change our kids' self-esteem or ideas about bodies overnight, it's a fight worth fighting.

This article was originally published on