Our Culture's Weight Obsession Wrecks Our Kids

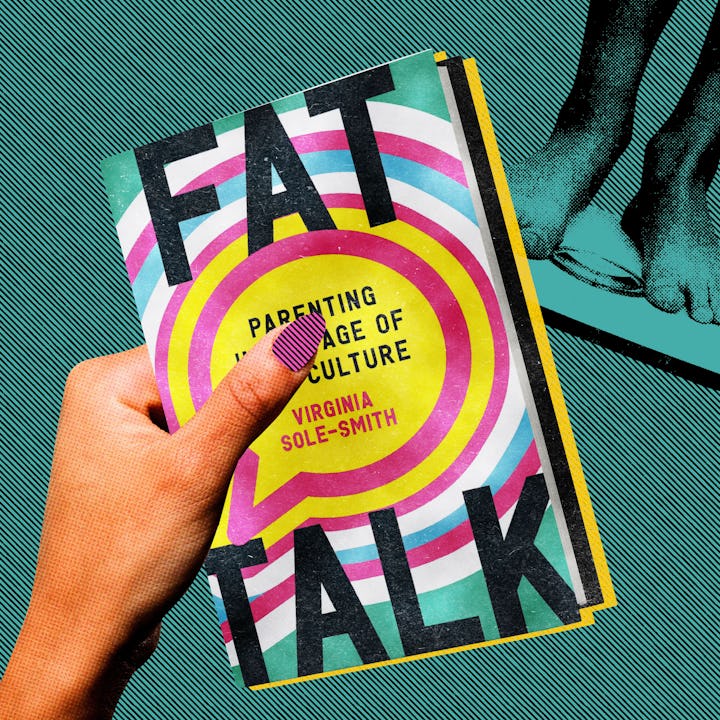

The new book Fat Talk: Parenting in the Age of Diet Culture dares us to stop weighing kids and ourselves, even at the doctor's office. The author asks, “What if our goal was to raise kids who trust their bodies?”

There's a lot to unpack in Virginia Sole-Smith's paradigm-shifting book Fat Talk: Parenting in the Age of Diet Culture. Her topline proposals: How about we stop letting kids be fat-shamed as if fat = bad? Can we quit policing our kids' "healthy eating" in a way that sets them up to feel like they can't trust themselves? What if mealtime with our kids was just social and we didn't control portions but instead let them eat whatever they want from what's on the table?

The terror for most American parents is that, given no guardrails, their children might constantly eat themselves sick on sugar and junk. But what's actually happening with our micro-managing is that kids sneak treats, gorge on candy if they get the chance, see vegetables as undesirable and, most heart-wrenchingly, understand that "fat" is a bad thing to be by the time they head to preschool.

I talked with Sole-Smith about some parts of the book that hit me, as a parent, the hardest.

Scary Mommy: You have this radical idea that we should stop weighing ourselves and our kids, even at the doctor's office.

Virgina Sole-Smith: With kids, it's more nuanced. There are times where you need to know their weight for the Tylenol dosing and car-seat sizes and things like that. And it's so important that kids gain weight every year: All kids, no matter what their body size, need to be growing. If they're losing weight, that can be indicative of a health problem. But, does my kid need to get weighed when we go in for an ear infection? Definitely not.

We could have doctors do a blind weigh-in at every well visit, with our kids not knowing the number. Doctors could talk privately to the parent if there's a concern about a big shift — it would make much more sense. Instead, every doctor's appointment we go to, as kids or as adults, ends up being super weight-centric in a way that does not promote health. Getting weighed first-thing centers the conversation in the wrong place. When I interview people, they so often say that a comment the pediatrician made was the event that triggered a disordered relationship with food.

[Weigh-ins, Sole-Smith contends, also prevent adults who feel bad about their size from going to their own well visits, potentially missing chances to catch conditions early purely because they dread the scale.]

SM: Another point that blew my mind, and that you might get pushback for, is the notion that perhaps someone who is overweight and has a stroke suffered that stroke due to a life of low-grade stress and shame in our thin-centric culture. The stress, in fact, could have caused more problems than extra pounds.

VSS: This is so controversial, and it shouldn't be. We should have better science to answer the question, but we don't because the bias is so baked into how research on weight and health gets done. Most researchers are taking it as a foregone conclusion that high body weight causes health problems. That's the premise from which they're doing all their investigations when, in fact, we don't have any studies showing causal relationships.

We have correlations, but we don't have causation. And that's a super important distinction to make. There are lots of explanations for disease that don't involve the literal pounds sitting on your body. It could be all the social determinants of health: experiences of poverty, lack of access to healthcare, lack of access to healthy food and nutrients. We know these things seem to contribute to larger body size, but it doesn't mean the body size then causes the health problems. It means maybe both body size and health problems are outcomes of these experiences.

The big thing we need to collect data on — but which isn't getting funding — is this question of "What is the physical toll of daily experiences of anti-fat bias?" The fatter you are, the more bias you experience as you move through the world. We have clear data showing that this raises cortisol levels, the stress hormone. So many people are living in a stress-response state all the time.

SM: Bringing this back to parents — what can we do? I want to mitigate any child's worry about their size. But we start parenthood by being handed a baby that we have to feed, and we kind of never stop believing their size is our job.

VSS: We have been told that our main goal as parents is to raise kids who eat their vegetables and who don't eat "too much." It's nutrition in service of thinness. You're eating a certain way in order to maintain a thin body. This creates unrealistic standards and is honestly not good for anyone's health.

My reframe is, what if our top priority in feeding our kids was body autonomy? What if our goal was to raise kids who trust their bodies, who know that their bodies are never the problem, no matter what size they are, no matter what the world's telling them, who have that bedrock of trust in themselves?

Currently, kids are more or less told that they don't get to listen to themselves. How are we expecting them to be able to trust themselves as teenagers, and into adulthood? If you change your focus around family meals to "This is my space to connect with my kid," then you're not counting broccoli bites or cookies. You're talking about other things and giving them breathing room. That's powerful, and that's love.

[Sole-Smith stresses that there's nothing magic about "family dinner," so if your only time to all sit together is at breakfast on Saturdays or during movie nights on Fridays, that works too.]

SM: Kids have a sharp radar. I feel like you cannot casually put down both cookies and salad and say, "Yum, salad's so good for our bodies," without kids knowing one food is now acceptable and one is a little bit forbidden.

VSS: It's so hard to keep all foods neutral. Kids completely read us when we get excited about them eating salad, and we tense up when they eat cookies. But I think if you can try giving your kids pretty unfettered access to foods that make you anxious — put down a plate of cookies and don't comment on how many people can have or how fast they're eating them — you can start to watch your kids really enjoy the food.

[You likely already give them unfettered access to fruits and healthy snacks. The goal here is to take the shame out of treats as well, to raise kids who eat without side-eying others to see if they are "allowed" to have more. Being judged trains them to listen to cues outside of their own body.]

SM: We're up against society. What are some ways we can give kids armor to all the comments people make about food and size?

VSS: Be a safe space so your kid can come home and talk about it. Often comments about size burn into our brains because nobody countered it. Nobody questioned it. Be the person who tells your kid, "Your body is amazing. No one deserves mean comments. Our culture sets us up to think our body is a problem, but it is not."

If you're there when a doctor or someone else makes a comment, jump in with, "I'm not really worried about that. I trust their body. I think their body's growing really well, and we're just not going to focus on that." Your kid cares more about what you think than what the doctor does.

Also, call out anti-fat bias in the media. Peppa Pig is so mean about Daddy Pig's tummy! [Even Bluey can be scale-obsessed.] I'm watching Gilmore Girls with my 9-year-old right now, and we love it, and I love Melissa McCarthy's character in it, but there are a lot of eating jokes. I just keep yelling, "You don't have to think that way! It's OK to eat." And my 9-year-old is eye-rolling along with me. Now she'll often bring me examples that she finds in a book or a video game. She'll show me and be like, "Look at this, Mom. It's diet culture."

This article was originally published on