What I Said When I Had The Other Talk With My Black Daughter

I knew it was coming.

Black daughters felt like dodging a bullet. I had been terrified of birthing a Black son. Of fiercely loving a Black boy. Of being rewarded for that bottomless love with a hole. Of having to watch his back as it walked out of my front door. Of having “the talk” with him and hating myself for it.

Whether you’re woke or hitting the snooze button under a post-racial rock, you’ve heard of “the talk.” It’s the sit-down we have with our children — usually preteen sons — about how to contort and comport themselves around the police. “The talk” is both a necessary survival tactic and a macabre rite of passage, meant to protect our boys from the immediate physical dangers of racism while welcoming them into Black manhood before any child should begin packing away their childish things. Sure, you still sleep on PJ Masks sheets, but it’s past noon on your boyhood, and these racist adults are waiting patiently outside. Mazel tov!

It’s your duty as a Black parent to deliver it. It’s not an option; it’s an obligation. Passed down from generation to generation for centuries, the talk has no script but can be recited by most. It’s a fact of Black life that white people have “discovered” in recent years. It has its own Wikipedia page. A dedicated entry on WebMD. And I thought that having a girl was equal to a hall pass — or at least a “let me tell you all about racism” rain check. A girl would be a welcome breeze.

I know, I know. The sense of relief was like sand through my fingers. Black women have had it every way but easy in America. But for that painfully brief moment in the doctor’s office, the idea of a girl child was a balloon. Then, of course, she landed earth-side and I had to share her with the rest of the world, i.e., those fucking girls. Girls (and boys, but come on, it always starts with girls) who, from the time they can talk and walk, possess the power to rip apart the concrete confidence I’ve been pouring into my daughters since before I knew them. Tiny wolves, dressed in little girls’ clothing, who I recognized from my own childhood (and from college and the office and the marches). Girls whose otherwise typical mean-girl in-training behavior wouldn’t grate so much if it weren’t directed at the only Black girl. So cue that other talk. The one I didn’t see coming until it was already giving me some serious stank eye from a pink Schwinn.

This is the story of why I told off a six-year-old — and would do that shit again.

Let’s start with Sally. To truly understand my firstborn and why I — an adult on paper — would get into it with a kindergartener on her behalf, we must blame her father. She’s his mini-me in more ways than one. Much like Rob, Sally has never once met a stranger. All unknown members of the animal kingdom are friends-in-waiting, folks who don’t know how much they missed Sally’s high- pitched “Hi!” until they hear it for the first time. Without filter or fear, she bum-rushes new “best friends” within seconds of meeting them. It’s all cute until my baby gets stiff-armed by a six-year-old who’s reached her buddy limit for the day. Sally, though, is rarely deterred by something as intangible as boundaries. God, it’s delightful and painful to watch from a park bench. I usually let these abbreviated morality plays run their course — the kid in question eventually gives up and in. Except when the object of Sally’s unrequited affections is white. For reasons both personal and problematic, I cannot stand it when my daughter chases after little white girls at the park who want nothing to do with her. My Black Mama hackles rise, and I go into attack mode.

On the afternoon in question, I’d had enough. Sally was running behind a little asshole dressed in an Elsa costume. Okay, okay, asshole is harsh. The girl was fine, I guess. She had a flat curtain of auburn hair cut in a sharp edge along her shoulders and all the assuredness of a kid wearing glittery high-tops, polka-dot leggings, and a well-loved princess dress. Sally, a Frozen-head, was smitten. From my perch at a bench not far away I watched nervously as my daughter did what she does.

“Hi! My name’s Sally,” she huffed cheerily while running alongside this little girl who was so clearly ignoring her. Undeterred, Sally kept at it, following this silent child from swing to slide, and trying her damnedest to get her attention. “Do you like Olaf? I like Olaf!” The girl stared through my child as if she didn’t exist—and maybe to her she didn’t. There was clear evidence of Little Elsa’s ability to laugh and play. She’d been doing plenty of both with another kid when we arrived. But add Sally to the mix and now the recipe for good old-fashioned fun was somehow ruined. She looked at my daughter, my radiant child, as if she were radioactive, immediately running in the opposite direction whenever Sally got close. It goes without saying that to my big-girl eyes (and baggage) Sally’s skin was the kryptonite. There are other Black kids besides mine in our neighborhood (I know because we’ve conscripted nearly every one of them), but unless we intentionally roll deep to the playground, they’re almost always outnumbered. It wouldn’t be shocking for Elsa to not have any real Black friends. For her to see my daughter as an unknown, a non-factor, a problem to be ignored. Before Sally can launch into her smooth-jazz rendition of “Let It Go” and things really go off the rails, I step in.

“Sally. Sally. Come here, butter bean,” I call.

“Mommy, my new friend has an Elsa costume. Elsa!”

“That’s not your friend,” I deliver bluntly, hoping not to sound too harsh, but Band-Aids need ripping. “That’s just some girl in a dress. You have friends. Vivienne, Zora, Zola, Kai, Malcolm, Mackenzie, Winter, Sadie . . .” I rattle off every brown-skinned child Sally has ever known, reminding her she’s got people. “She is my friend!” Sally announces defiantly, before running in Elsa’s direction once again. I back off but not away, squinting across the artificial turf for any sign of something not right. Sally repeatedly tries and fails to get Elsa’s attention. Okay, this kid is an asshole. I’m sorry. She’s gone from aggressively snubbing my child to baiting her, basking in Sally’s attention then hopping on her pink bike and pedaling away just as Sally gets close. Finally, my baby girl is starting to get it, and goes to sulk by the swings with her head hanging low. Have you ever seen a child with the shoulders of defeat? Oh, it’s a gut punch. I was on my way to deliver a pep talk when Elsa comes at me, bro. Like, she legit pulls up. Let me repeat: This six-year-old pedals full speed in my direction and stops short with a screeching halt and stares me down like she’s tryna start some shit. Oh, honey. We can do this if you want to.

Hand on my hip, I dramatically cock my head to one side, “Hello.”

The child says nothing. She just keeps glaring at me like she’s waiting for an apology. Who is this kid?

“Hel-looooo,” I repeat a little louder. “It’s polite to speak when spoken to. Didn’t your mother teach you that?”

She mumbles something and I hit another meme-able move, rotating my stank face so that my ear can hear her. “Excuse me? What did you say?”

“Hi,” she whispers in a tone that’s more self-satisfied than shy, and she’s still drilling holes with her eyes. Did I mention she was six, maybe five? I did. Okay. “I said ‘Hi.’ ”

“Ummhmm,” I grump through pursed lips my aunties would applaud. “It’s also polite to greet new friends or at least let them know you’d like to play alone. But don’t worry, Sally’s good. She is very fun and we’re going to have a great time on the swings. Good day!”

Then I jog over to my daughter, who is still moping, and commence to show her the time of her little life at that playground. And all the while I narrated each moment like a Greek chorus for an audience of one — Elsa.

What teachable moment was I trying to impart to my daughter and this four-foot tyrant? That Black is beautiful? That children are ready for Critical Race Theory? That I am ready to flip cars and kindergarteners should they pose a threat to mine? All of it.

Our own baggage as former little Black and brown girls looking for love in all the white spaces. None of us came out unscathed, and in trying to save our children from the same scars we question whether we’re helicoptering too close. Because, come on, all children can be irrational maniacs. Anyone who’s spent an hour explaining to a snot-sobbing four-year-old that she can’t wear those dirty-ass rain boots to school knows this. But it’s not just in our imagination.

There are reams of research pages dedicated to racial preference among children. Babies as young as three months can spot physical differences and prefer the faces of certain racial groups, i.e., the folks they know. Duh. As they begin to make sense of their expanding world, older and more mobile babies use race to categorize, grouping like with like. Again, completely logical. But as the months and years pile up, so do the potential land mines. By three years old, some kids start associating certain characteristics and behaviors with certain racial groups. Ruh-roh! In the United States a four-year-old has the mental capacity to associate white skin with wealth. By kindergarten white kids in America demonstrate strong “in-group” bias, meaning they prefer other white kids over every- body else. Black children the same age, however, don’t show that same level of racial preference. Surprised? I’m not.

The talk? More like talks, or the talk that never ends. We prep for it. We’ve spent a lifetime gathering notes. And yet, when it arrives it takes our breath away. “I wish my face was different,” Sally tells me one morning while inspecting herself in the bathroom mirror.

“Huh?” I manage, nearly choking on the pink-flavored Paw Patrol toothpaste she’d begged me to try. Damn. We’re here? Already? Baby girl continues examining her contours with that psycho intensity only four-year-olds can pull off — caressing her tawny cheeks with her tiny hands and making long Os with her mouth to stretch every inch of her perfect skin.

Still staring at her reflection, my child says, “I want my skin to be another color.”

Ring the alarm! Someone alert whatever secret MIB-type agency revokes Black Mama cards because, guys, I have failed! This baby, who I have purposefully placed in a Black-girl-magic echo chamber with Beyoncé surround sound, wants Different. Colored. Skin. What do I do? Who do I call? Where are the instructions?

“Goose, what are you talking about? Your skin is everything! It’s brown like Mommy’s. Like Yaya’s. Like Memaw’s,” I counter, trying not to sound hysterical. “It’s beautiful.”

I swear my heartbeat slows in anticipation of the dagger. The water filling up the bathroom sink for Sally’s morning “experiments” stops rising. The wind blowing in from the rip in the win- dow screen pauses. This is it, I think. This is the moment when my beautiful baby girl tells me she wants to be white, and I die inside. “What other color would you want it to be?”

My daughter slowly turns to face me and delivers her answer with a devilish grin: “Purple.”

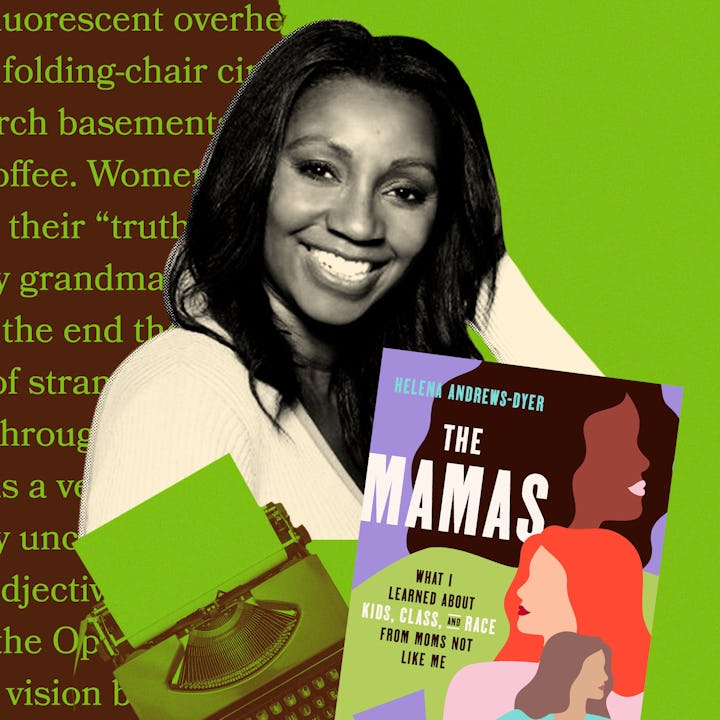

Adapted from the book THE MAMAS: What I Learned About Kids, Class, and Race from Moms Not Like Me by Helena Andrews-Dyer. Copyright © 2022 by Helena Andrews-Dyer. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Helena Andrews-Dyer is a senior culture writer at The Washington Post. She is the author of Reclaiming Her Time as well as Bitch Is the New Black, which was optioned by Shonda Rhimes. Her work has appeared in O: The Oprah Magazine, Marie Claire, Glamour, and The New York Times, among other publications. Andrews-Dyer has appeared on ABC’s Nightline, CBS’s This Morning, CNN, MSNBC, SiriusXM, NPR, and NY1. She lives in Washington, D.C.

This article was originally published on